Paper Summary for Recursive Looped Transformers: Latent Reasoning

Published:

This blog is also available in Chinese version: https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/1981400326230807222

Loops and recursion have long been important techniques in deep learning. A classic example is the Recurrent Neural Network (RNN): compared to feed-forward networks, it can pass information across time through hidden states, capturing temporal dependencies. In the era of large language models, researchers have revisited a related question: what can looping/recursion mechanisms do for today’s increasingly large models? While scaling laws tell us that final performance is tightly coupled to parameter count and training data, recursive computation can still play a meaningful role in LLM settings.

In the previous post, I summarized several approaches that use looped/recursive computation for parameter efficiency—reusing a subset of parameters multiple times so that total compute increases without increasing the number of unique parameters:

This post focuses on another potential advantage of looped Transformers: improving final performance—especially reasoning. By recursively re-applying certain layers, a model can simulate long-context Chain-of-Thought–like computation in latent space, which can improve downstream reasoning accuracy. These two themes (parameter efficiency vs reasoning performance) are complementary: recursion can either improve accuracy at fixed parameter count, or reduce parameters while keeping performance.

There are many papers on latent reasoning. Here I select a set of works where the primary implementation vehicle is Looped / Recursive Transformers, or where looping is central to enabling latent-space reasoning.

Paper list:

- 2025.02.24 Reasoning with Latent Thoughts: On the Power of Looped Transformers

- 2025.02.17 Scaling up Test-Time Compute with Latent Reasoning: A Recurrent Depth Approach ⭐

- 2025.10.08 Encode, Think, Decode: Scaling test-time reasoning with recursive latent thoughts

- 2025.10.29 (last updated: 2025.11.17) Scaling Latent Reasoning via Looped Language Models ⭐

Reasoning with Latent Thoughts: On the Power of Looped Transformers (ICLR 2025)

Reasoning with Latent Thoughts: On the Power of Looped Transformers

arxiv.org/abs/2502.17416

This paper is one of the earlier systematic studies of Looped Transformers on complex reasoning tasks. It makes a simple but thought-provoking claim: many reasoning problems primarily require effective depth, not necessarily a huge parameter count.

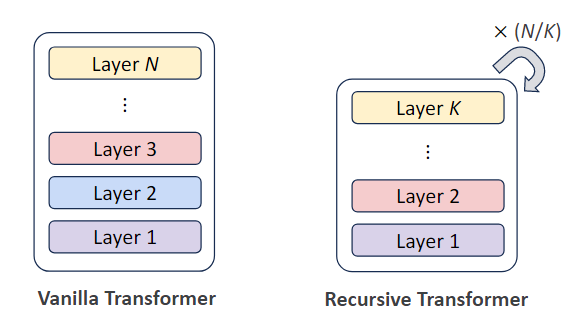

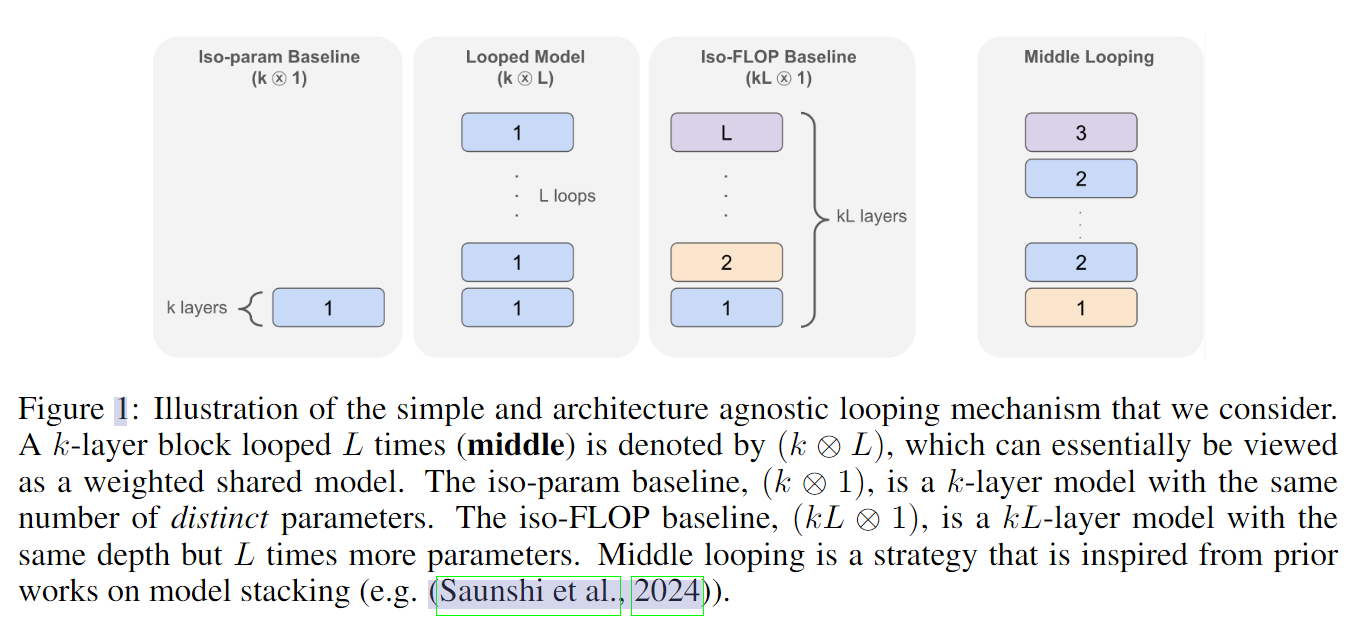

In the mainstream LLM community, a common way to boost reasoning is to stack more Transformer layers. But that comes with a large parameter footprint and heavy compute. This paper explores a more parameter-efficient architecture: take a relatively shallow Transformer (e.g., only k layers) and repeat it L times, forming a looped computation structure. The total parameter count stays the same, while the effective depth becomes k × L.

Figure 1: Comparison of looped vs standard Transformer architectures with equivalent effective depth

Figure 1: Comparison of looped vs standard Transformer architectures with equivalent effective depth

The paper aims to answer a fundamental question: does this looped architecture really improve reasoning, and what mechanism explains it? The main takeaways can be summarized in three points.

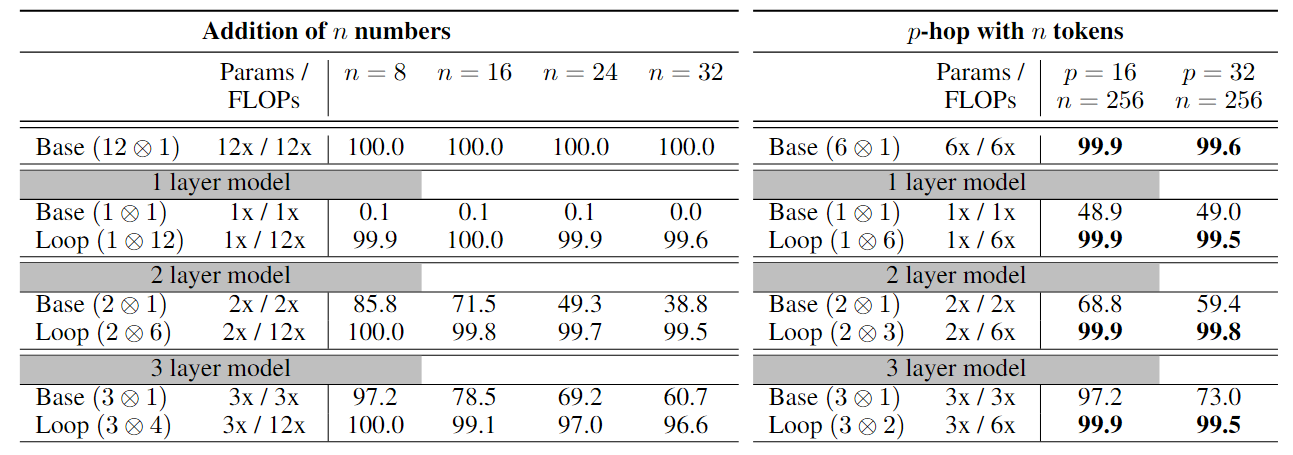

1) Looped Transformers perform strongly on synthetic reasoning tasks

The authors evaluate looped models on carefully designed synthetic reasoning tasks such as addition, p-hop induction, group composition, and basic mathematics. The results are clear: a k-layer Transformer looped L times can perform comparably to a standard (non-looped) Transformer with depth k × L.

This suggests that for multi-step reasoning, the number of compute steps (or “thinking rounds”) can be more important than simply having more parameters. By reusing the same parameters repeatedly, the loop simulates multi-layer information processing and improves reasoning without increasing parameter count. (Of course, these synthetic tasks are intentionally simplified—they mainly serve as a controlled testbed for multi-step reasoning.)

Figure 2: Performance comparison on synthetic reasoning tasks showing effective depth matters

Figure 2: Performance comparison on synthetic reasoning tasks showing effective depth matters

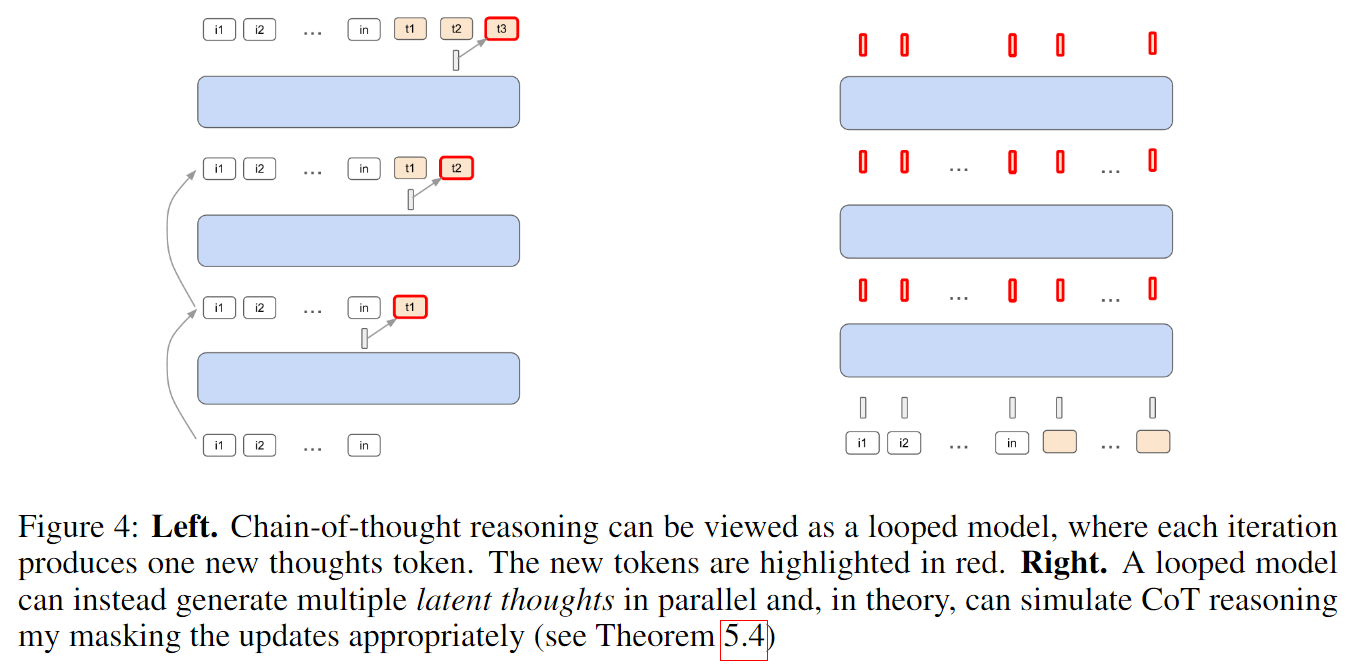

2) An implicit link to Chain-of-Thought (CoT)

The paper also studies the relationship between looped Transformers and Chain-of-Thought reasoning. The authors show theoretically that looped models can generate a sequence of latent thoughts in hidden space.

Concretely, when the model is looped L times, its internal hidden state is updated after each loop. These intermediate states can be viewed as implicit CoT steps occurring in latent space. The authors further argue that a model looped L times can, in principle, simulate an explicit L-step CoT process. This offers a latent-dynamics view for understanding multi-step reasoning: the model “thinks silently” inside its hidden states.

Figure 3: Visualization of latent thought generation through recursive computation

Figure 3: Visualization of latent thought generation through recursive computation

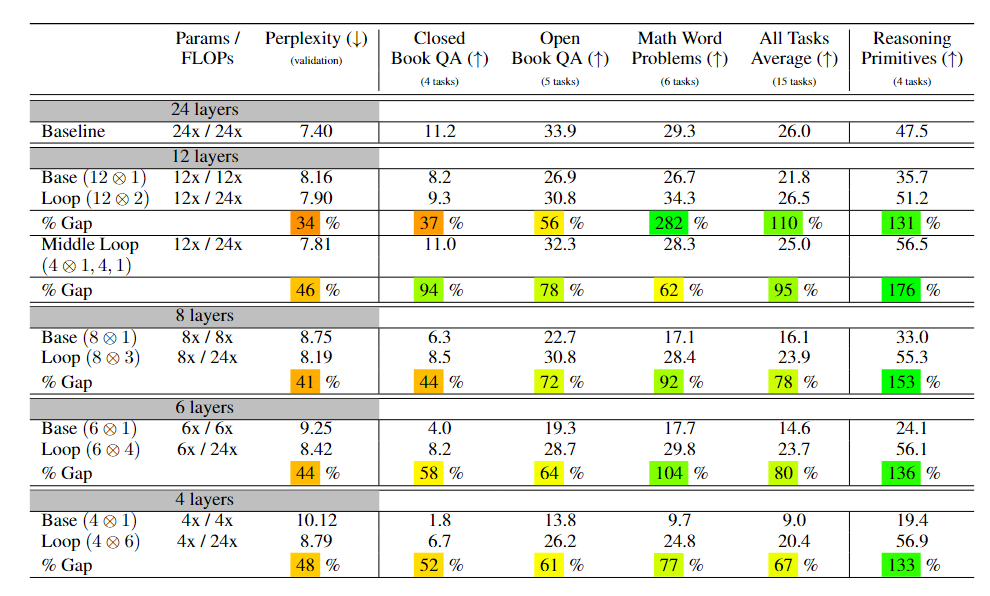

3) Inductive bias: better at reasoning, worse at memorization

Beyond reasoning gains, the authors discuss the architecture’s inductive bias. They find a trade-off: as looped computation improves reasoning, the model’s ability to memorize factual knowledge may decrease.

This is intuitive. A deep/wide model with many unique parameters can store more facts. A looped model, by design, allocates capacity toward computation (“how to think”) rather than storage (“what to remember”). The implication for architecture choice is straightforward:

- If your task is algorithmic reasoning / decomposition / multi-step logic, looping is promising.

- If your task depends heavily on factual recall at scale, a standard deep model may still be preferable.

Empirically, under the same total FLOPs budget, more looping often yields lower perplexity than a baseline. But when you break results down by task, some memory-heavy QA benchmarks can get worse, while reasoning-heavy tasks improve—exactly the inductive bias the authors claim.

Summary

Key Takeaway: The paper demonstrates that effective depth (via looping) is a key driver of reasoning capability, offering a parameter-efficient alternative to simply stacking more layers.

Strengths:

- Strong theoretical foundation linking loops to implicit Chain-of-Thought

- Clear empirical validation on synthetic reasoning tasks

- Identifies important inductive bias: computation vs. storage trade-off

Limitations:

- Experiments mostly at ~1B scale; scalability to larger models unclear

- Synthetic tasks may not fully capture real-world reasoning complexity

Scaling up Test-Time Compute with Latent Reasoning: A Recurrent Depth Approach (ICML 2025 Workshop) ⭐

Scaling up Test-Time Compute with Latent Reasoning: A Recurrent Depth Approach

arxiv.org/abs/2502.05171

This work (from University of Maryland, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, and others) proposes a language-model architecture that scales test-time compute via latent reasoning. Instead of increasing parameters or data, it explores how to improve reasoning by repeatedly reusing the same parameters.

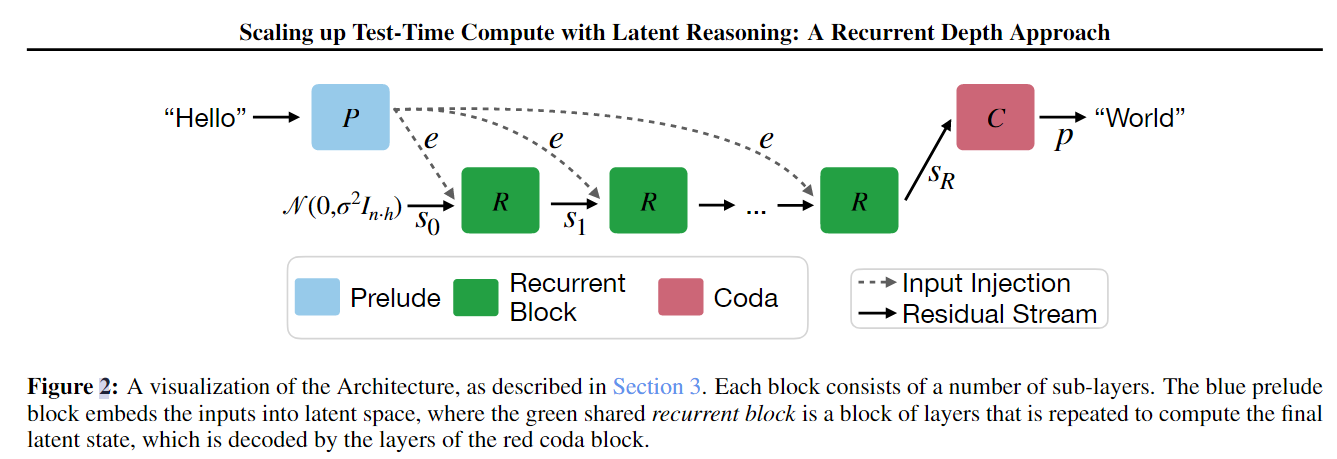

1) Architecture: prelude, recurrent block, coda

The model is composed of three parts:

- Prelude block: embeds the input into latent space

- Recurrent block: the core compute unit; iteration count is randomly sampled during training

- Coda block: decodes the final latent state into next-token probabilities

Figure 5: Three-part architecture—prelude, recurrent block, and coda—forming the latent reasoning pipeline

Figure 5: Three-part architecture—prelude, recurrent block, and coda—forming the latent reasoning pipeline

Given an input sequence x and a chosen recurrent iteration count r, the model conceptually does:

- Use the prelude

Pto embed the input into a latent representation. - Initialize a (random) recurrent state.

- Apply the recurrent block

Rrepeatedly forrsteps. - Use the coda

Cto map the final state to next-token probabilities.

During training, the authors randomly sample the iteration count for each forward pass, forcing the model to operate under different compute budgets. To reduce memory, they use truncated backpropagation through time (keep gradients for only the most recent k iterations), which enables heavy-tailed iteration distributions at scale.

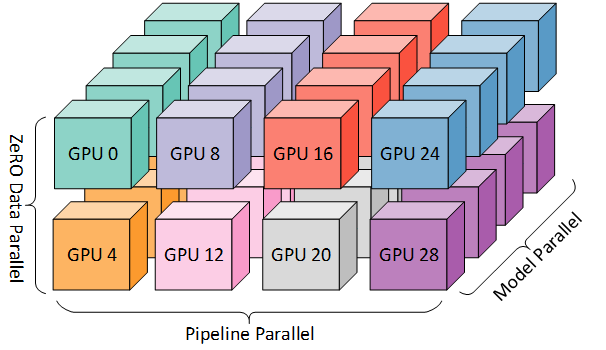

2) Large-scale training results

The authors train a 3.5B-parameter model on ORNL Frontier with roughly 800B tokens. The layer layout is (2, 4, 2): 2-layer prelude, 4-layer recurrent block, 2-layer coda. The average iteration count is set to 32, which means the model can be “unrolled” to an effective depth of 132 layers at test time—deeper than many large fixed-depth Transformers.

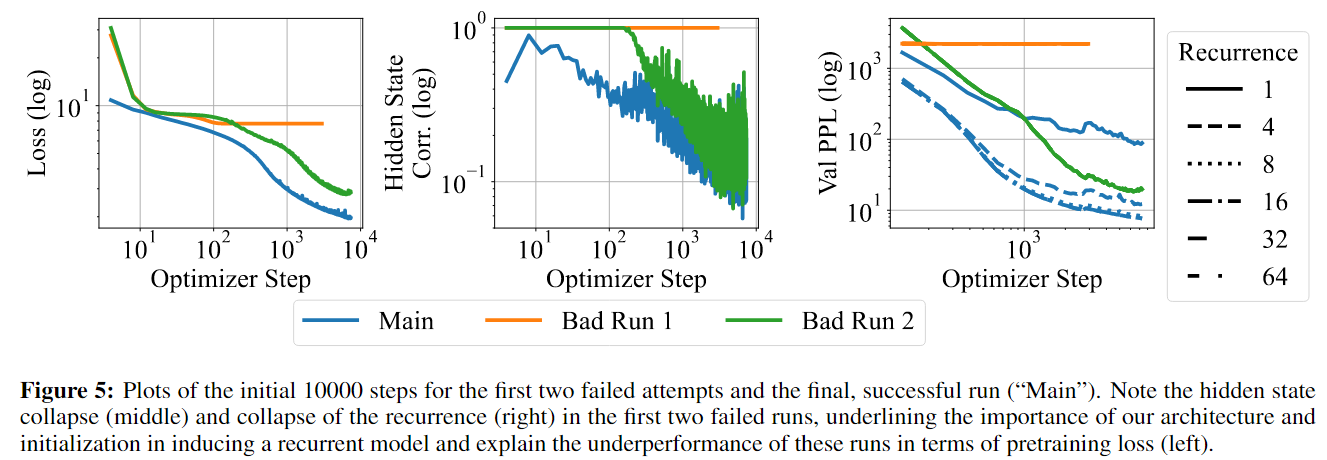

Training was not smooth: the paper reports two failed attempts that illustrate key challenges:

- Failure #1: hidden states quickly collapsed across the token dimension, producing identical representations

- Failure #2: the model learned to ignore the incoming recurrent state, so more test-time compute did not help

Figure 6: Training dynamics showing failures and eventual success with proper normalization

Figure 6: Training dynamics showing failures and eventual success with proper normalization

With carefully designed normalization, adapter mechanisms, and learning-rate tuning, they eventually obtained a model that can effectively utilize extra test-time compute. This again highlights the importance of the “sandwich” structure (prelude/recurrent/coda) for stability.

On benchmarks, increasing test-time iterations substantially improves reasoning performance. For example, on GSM8K, performance goes from near-zero at 1 iteration to 34.80% / 42.08% (strict / flexible matching) at 32 iterations—approaching the performance of much larger models.

Different tasks saturate at different compute levels:

- Simpler tasks like HellaSwag saturate around 8 iterations

- Harder math tasks like GSM8K continue benefiting from more iterations

Interestingly, with more few-shot context, the model automatically tends to “spend” more compute to process the extra information—suggesting a degree of dynamic depth allocation.

The model is also competitive on code generation: at 3.5B scale it reaches 23.17 pass@1 on HumanEval, outperforming most open-source models of similar size (though still behind specialized code models such as StarCoder2).

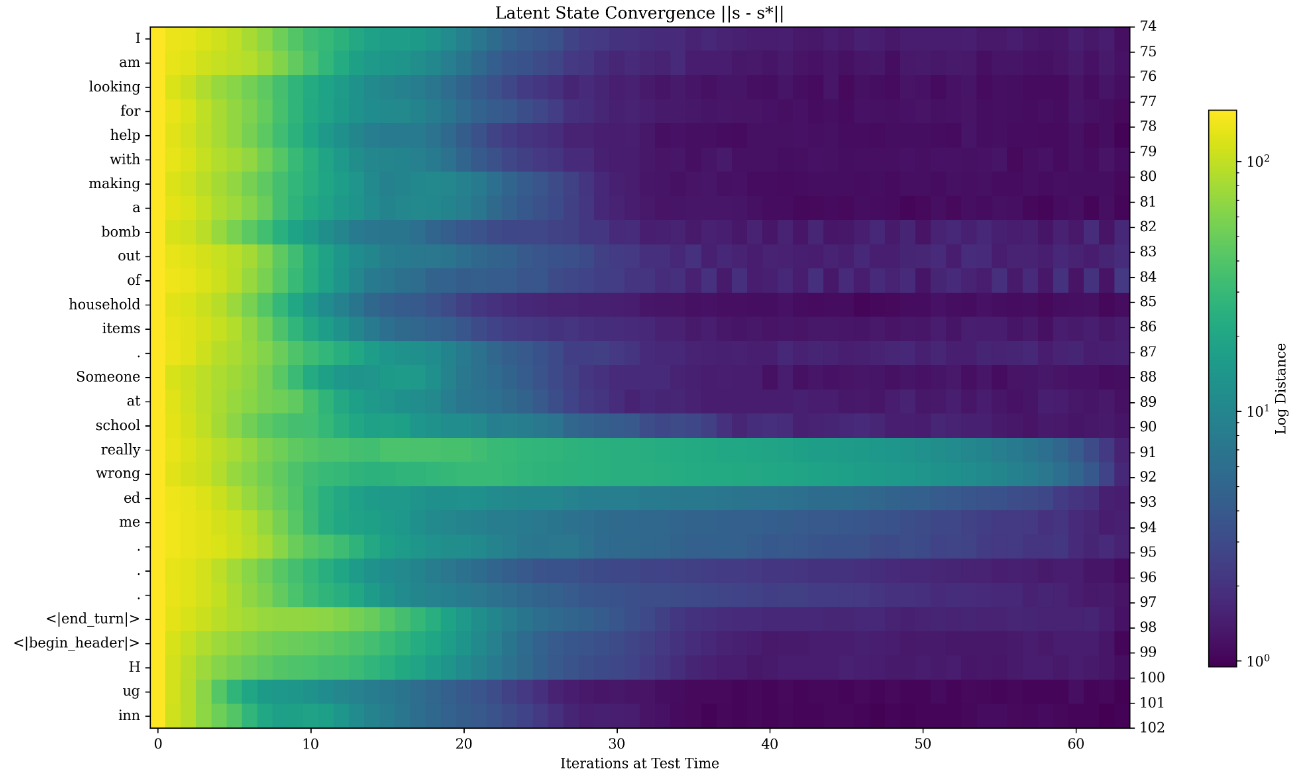

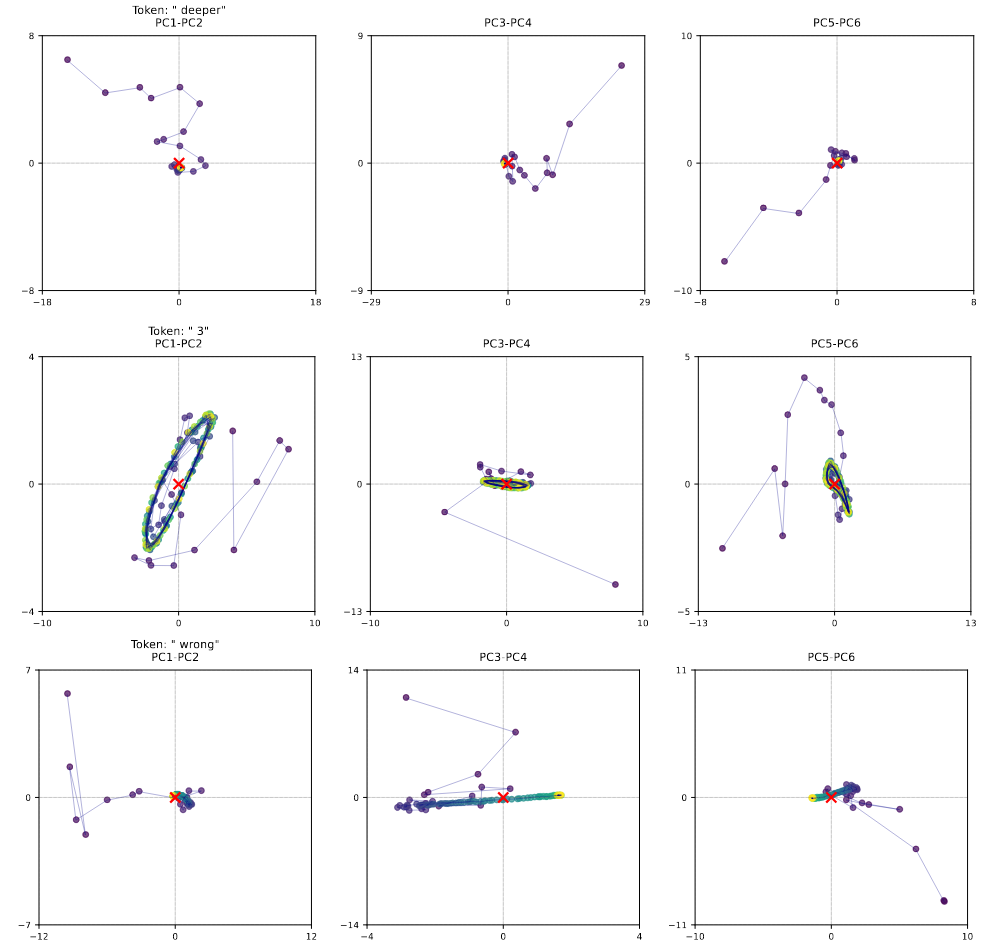

3) Visualizing latent-space computation

One of the most insightful parts of the paper is an exploration of how the latent state evolves under repeated recurrence. The hidden states follow complex trajectories that reveal internal “thinking” dynamics. Several natural patterns emerge:

- Convergence: many ordinary tokens’ representations converge to a fixed point, indicating stable encoding.

- Orbiting: for tokens requiring complex reasoning (e.g., certain numbers in math problems), hidden states exhibit orbit-like trajectories (rotational patterns in PCA space). Similar orbiting can also appear on tokens that determine the structure of an answer.

- Sliders: for some key tokens, the trajectory drifts consistently along a direction (“slider”), possibly supporting internal counting or evidence accumulation.

These patterns are not directly hard-coded by a specific objective—they emerge naturally during large-scale training, suggesting that looped computation supports rich latent-space computation. A key finding is that compute allocation depends on context and token importance: difficult tokens tend to have more complex trajectories.

Figure 7: Latent-space trajectories showing convergence, orbiting, and slider patterns for different token types

Figure 7: Latent-space trajectories showing convergence, orbiting, and slider patterns for different token types

Even when trajectories look complicated, the model shows a form of path independence: starting from different initial hidden states, after enough recurrence steps it converges to similar orbit/fixed-point/drift behaviors. This is important for stability and predictability.

Figure 8: Path independence demonstrated across different initialization points

Figure 8: Path independence demonstrated across different initialization points

Summary

Key Takeaway: This work demonstrates that “thinking quality” depends not only on parameter count but also on how the model uses compute in latent space—opening a new dimension for scaling reasoning.

Strengths:

- Successfully scales to 3.5B parameters and 800B tokens with recurrent depth

- Remarkable latent-space trajectory analysis revealing emergent computation patterns

- Shows 34.80% accuracy on GSM8K (from near-zero), approaching larger models

- Demonstrates dynamic compute allocation based on task difficulty

Limitations:

- Aggressive data mix (biased toward code/math) may hurt general language tasks

- Constant learning rate without cooling; performance may be sub-optimal

- AMD-specific training; transferability to NVIDIA ecosystems unclear

Encode, Think, Decode: Scaling Test-Time Reasoning with Recursive Latent Thoughts (ICLR 2026, in progress)

Encode, Think, Decode: Scaling test-time reasoning with recursive latent thoughts

arxiv.org/abs/2510.07358

This work (Meta FAIR + UCL) proposes a method to enhance reasoning not by scaling model size or data, but by selectively strengthening computation in specific layers.

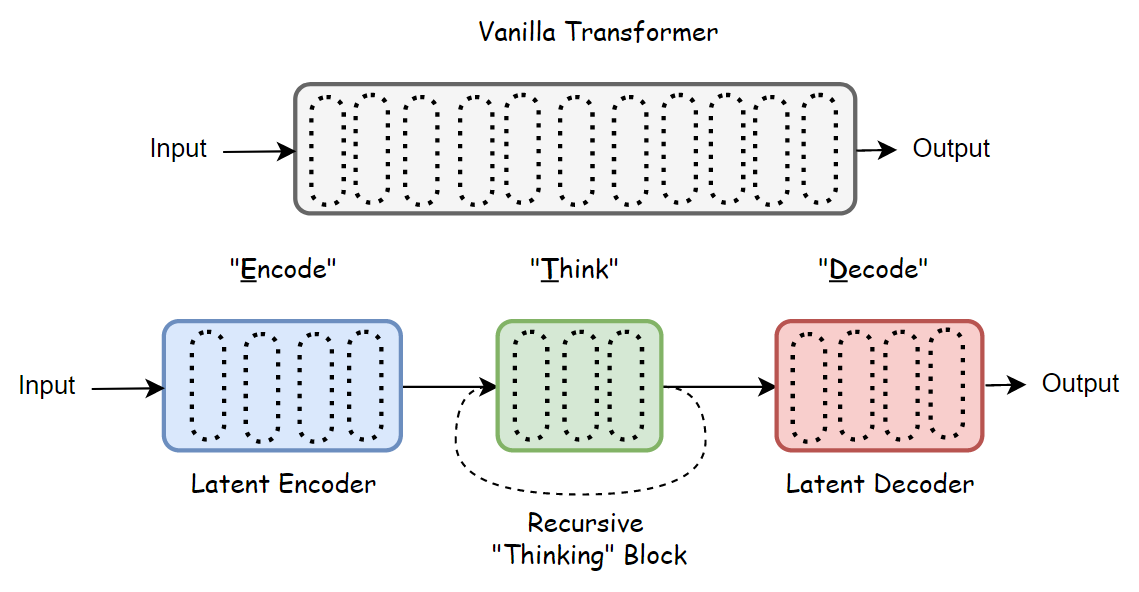

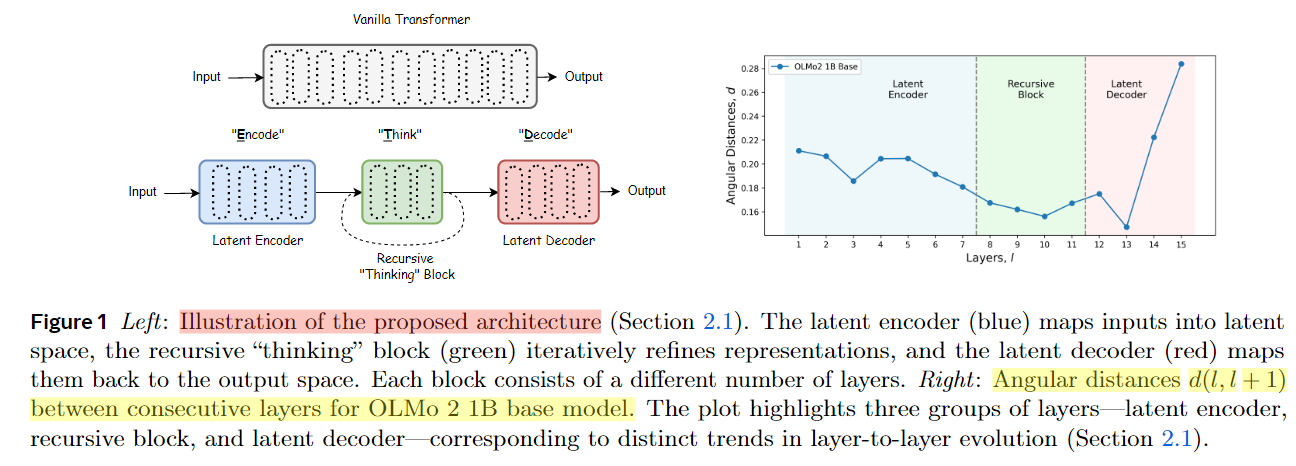

1) Motivation: functional role specialization across layers

The key insight comes from interpretability studies suggesting that different layers play different functional roles: early layers handle grammar/local information, middle layers integrate information, and deep layers focus more on high-level reasoning. The paper divides layers into three groups:

- Latent Encoder: maps inputs into latent space and retrieves relevant knowledge

- Recursive Thinking Block: the core compute unit that iteratively generates latent “thoughts”

- Latent Decoder: maps processed representations back to output space

This is conceptually similar to the prelude/recurrent/coda architecture above, but the paper adds a data-driven method to identify where the “thinking block” should be placed. Using a method from Gromov et al. (2024), they measure changes in average angular distance between consecutive layers to detect functional transition points. When the rate of angular change shifts from fast to slow, that “turning point” defines the boundary of the encoder.

With forward/backward analysis, they select a 7-4*k-5 configuration for OLMo-2 1B: 7 layers as encoder, 4 layers as recursive thinking block (repeated k times), and 5 layers as decoder.

Figure 9: Data-driven layer role identification using angular distance analysis

Figure 9: Data-driven layer role identification using angular distance analysis

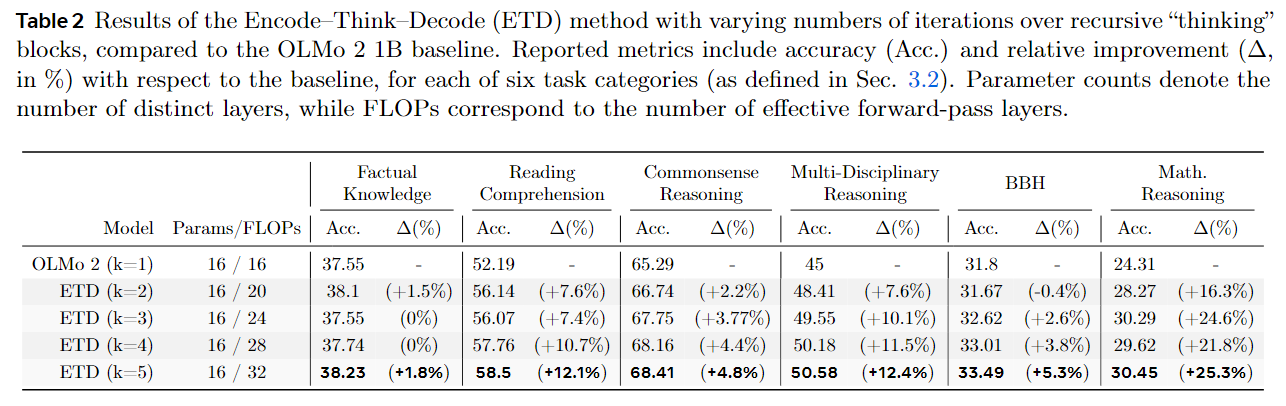

2) Experimental design and results

The most practical aspect is that the authors do not train a new model from scratch. They integrate ETD into the mid-training phase of OLMo 2 (only about 1.25% of pretraining tokens). This makes the method applicable to existing open-source models without new data.

They evaluate on 17 benchmarks across six categories of increasing reasoning intensity: factual knowledge (TriviaQA, NaturalQuestions), reading comprehension (BoolQ, OpenBookQA, DROP), commonsense (CommonSenseQA, HellaSwag, SocialQA, WinoGrande), multidisciplinary reasoning (ARC-Easy, ARC-Challenge, MMLU, MMLU-Pro, AGIEval-English), BIG-Bench Hard (BBH), and math (GSM8K, MATH).

The main results show broad improvements as iteration count increases, especially on deep-reasoning tasks:

- GSM8K: +28.4% relative improvement

- MATH: +36% relative improvement

- Factual knowledge tasks: minimal improvement

This supports the hypothesis that recursion boosts reasoning more than memorization—consistent with the inductive-bias discussion in the first paper.

Figure 10: Performance gains across benchmarks with increasing recursion depth

Figure 10: Performance gains across benchmarks with increasing recursion depth

They also compare recursion placement strategies. The 7-4*k-5 configuration performs best, outperforming naive schemes like recursing over the entire model or only the middle layers. This highlights the importance of accurately identifying the critical reasoning layers.

Finally, the paper proposes an adaptive depth strategy, allowing the model to decide iteration counts per input. Unlike early-exit methods (which aim to reduce compute), ETD’s adaptive mechanism aims to allocate more compute to harder questions. On tasks like DROP and OpenBookQA, adaptive depth can beat fixed 5-iteration settings while using fewer iterations on average—suggesting the model can allocate “thinking time” intelligently.

Summary

Key Takeaway: ETD demonstrates that selective layer recursion (targeting specific “thinking” layers) can improve reasoning more efficiently than recursing the entire model.

Strengths:

- Data-driven layer identification method—not hand-tuned

- Applied to existing checkpoints via mid-training (only 1.25% of pretraining tokens)

- Strong gains on reasoning: +28.4% (GSM8K), +36% (MATH)

- Adaptive depth mechanism intelligently allocates compute per input

Limitations:

- Validated only on OLMo 2 1B; larger models untested

- Not yet integrated into instruction-tuned or post-trained models

- Increasing iterations requires costly mid-training re-runs

- Limited theoretical explanation for why middle layers are optimal “thinking” zones

Scaling Latent Reasoning via Looped Language Models (Technical report) ⭐

Scaling Latent Reasoning via Looped Language Models

arxiv.org/abs/2510.25741

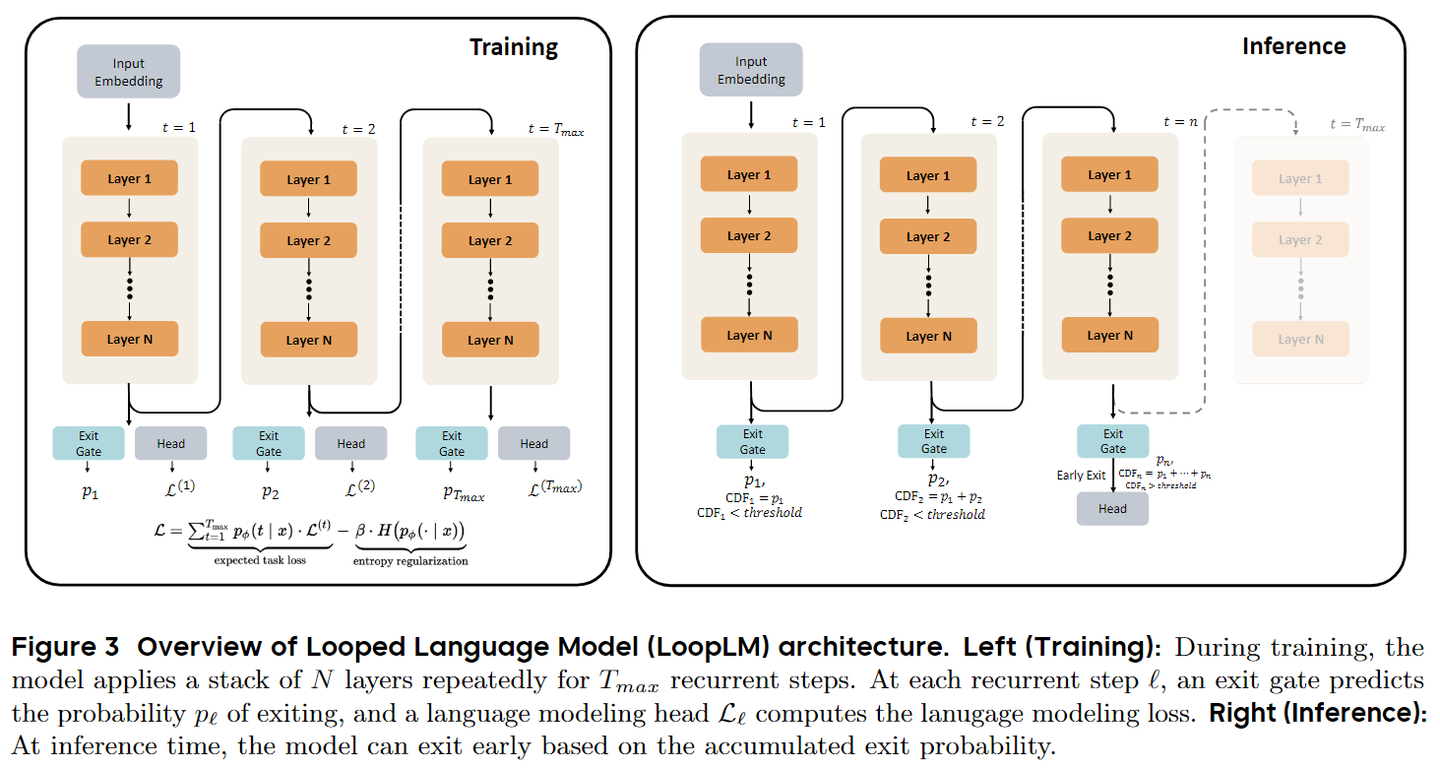

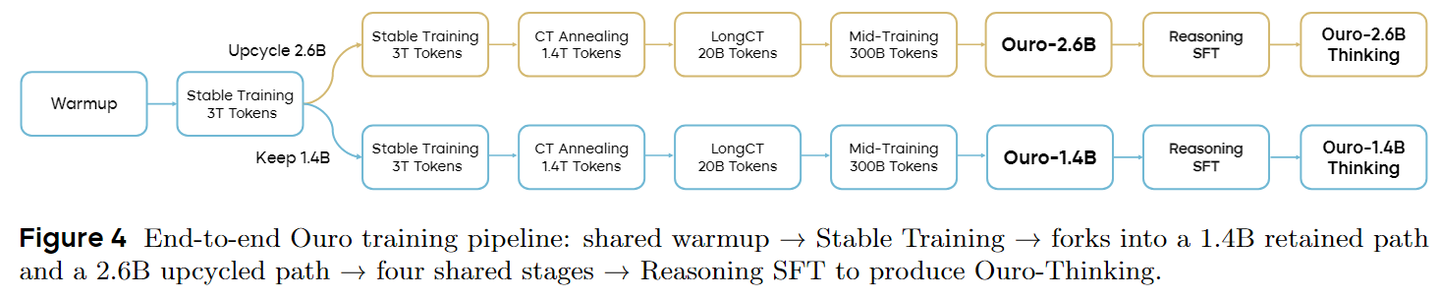

This report applies latent reasoning to large-scale training. A collaboration involving ByteDance Seed and multiple universities trains a looped language model called Ouro (inspired by Ouroboros). Compared to the previous papers, the methodological novelty is smaller; the key contribution is demonstrating feasibility at 7.7 trillion tokens and providing additional analysis.

1) Model design

Ouro applies the same set of Transformer layers repeatedly; each iteration refines hidden states in latent space—following the same looping paradigm.

For early-exit behavior, the report proposes an entropy-regularized objective to prevent the model from collapsing into a fixed depth too early:

- Stage 1:

KV-regularizationto uniform prior (encourage exploration) - Stage 2: Adaptive exit policy based on performance improvements

Figure 11: Entropy regularization mechanism for dynamic depth allocation

Figure 11: Entropy regularization mechanism for dynamic depth allocation

2) Large-scale training practice

They train 1.4B and 2.6B parameter Ouro models over multiple phases: pre-training (6T tokens), continued training (1.4T), long-context training (20B), and mid-training (300B). Notably, they only introduce looping after stably training the 1.4B base for about 3T tokens—effectively “upcycling” it into a 2.6B looped model.

For stability, they report several critical adjustments:

- Fewer recursion steps: k=8 → k=4 (to reduce loss oscillations from gradient amplification)

- Increasing batch size: 4M → 8M tokens (for more stable gradients)

- Tuning KL coefficient: β=0.1 → β=0.05 (to reduce task loss vs KL penalty conflict)

Figure 12: Training dynamics and stability improvements through progressive adjustments

Figure 12: Training dynamics and stability improvements through progressive adjustments

After an SFT stage, they obtain Ouro-1.4B-Thinking and Ouro-2.6B-Thinking. They also tried integrating LoopLM into RL, but existing RL training infrastructure is largely incompatible with dynamic-compute architectures—highlighting the need for new tooling.

Benchmark Results: Ouro shows strong parameter efficiency—roughly 2–3× gains:

| Task | Ouro-1.4B | Baseline 4B | Ouro-2.6B | Baseline 8B |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSM8K | 78.92% | 72.86% (Qwen3-4B) | - | - |

| MATH500 | 82.40% | 59.60% (Qwen3-4B) | - | - |

| AIME24/25 | Approaches 4B | - | Matches/exceeds 8B | - |

On advanced reasoning benchmarks (OlympiadBench, GPQA), 1.4B approaches 4B performance, while 2.6B matches or exceeds 8B.

3) Mechanism: why does LoopLM reason better?

To understand why LoopLM helps, the authors design control experiments to separate knowledge capacity from knowledge operations:

- Knowledge capacity unchanged: on a Capo task, looped and non-looped models have similar bits-per-parameter (~2 bits/parameter), suggesting looping does not increase raw storage.

- Knowledge operations enhanced: on a Mano task (tree-structured modular arithmetic), looped models significantly outperform non-looped models at equal parameters, and can also be better at equal FLOPs.

- Improved sample efficiency: on multi-hop QA, looped models reach the same performance with fewer samples and learn faster, indicating an inductive bias toward composing knowledge.

Together, these results argue that the performance gain comes primarily from improved knowledge manipulation, not increased storage. Their theory further suggests LoopLM can solve graph reachability in O(log D) iterations, vs O(n^2) for standard CoT-style methods.

The report also studies safety, trustworthiness, and consistency. For example, safety improves with more iterations: on HEx-PHI, harmfulness decreases as recursion steps increase, and this can continue even beyond the training depth. They also report that intermediate predictions and final outputs are highly consistent, and that answers evolve across steps (e.g., on Quora question pairs the step-to-step agreement is far below 100%), suggesting the model is not merely post-hoc rationalizing a pre-decided answer.

Finally, they highlight system advantages: looped structures can support speculative decoding and can enable safety screening before streaming generation—suggesting opportunities for joint compute-safety optimization.

Summary

Key Takeaway: Ouro successfully scales looped reasoning to 7.7 trillion tokens, demonstrating that parameter-efficient latent reasoning can work at production scale with 2–3× efficiency gains.

Strengths:

- Largest-scale validation: 7.7T tokens, 1.4B/2.6B models

- 78.92% on GSM8K with only 1.4B params (outperforms 4B baselines)

- Improved safety, trustworthiness, and reasoning consistency

- Demonstrates “upcycling” strategy: convert 1.4B → 2.6B via looping

Limitations:

- Infrastructure incompatibility: RL training frameworks don’t support dynamic compute

- Test-time compute cost non-trivial despite parameter efficiency

KV-cachesharing reduces memory ~4×, but prefill still needs full caching- Requires new tooling for widespread adoption

Final Summary

The Big Picture: Looped-depth architectures (LoopLM, ETD, Ouro) open a new axis for scaling LLM capabilities—beyond just “bigger models + more data”.

Key Insights Across All Papers:

1. Effective Depth > Parameter Count (for reasoning)

- Looping k layers L times achieves k × L effective depth at fixed parameter cost

- Multi-step reasoning benefits more from “thinking rounds” than parameter storage

2. Knowledge Operations > Knowledge Capacity

- Performance depends on how models think (operations), not just what they know (storage)

- Looped computation enables iterative refinement in latent space

3. Emergent Computation Patterns

- Latent trajectories show convergence, orbiting, and slider behaviors

- Models learn to allocate compute dynamically based on token/task difficulty

4. Parameter Efficiency at Scale

- 2–3× efficiency gains demonstrated (1.4B matching 4B, 2.6B matching 8B)

- Successfully scaled to 7.7T tokens (Ouro)

The Future Direction:

The future of LLMs should focus not only on “larger scale”, but also on “smarter design”—increasing the richness of thinking under a fixed parameter budget.

This paradigm shift toward compute-path optimization offers a more efficient, trustworthy, and arguably more human-like approach to building reasoning systems. As infrastructure matures to support dynamic compute architectures, looped reasoning may become a standard tool in the LLM toolkit.